Two weeks visiting schools across China offered an eye-opening comparison to our own education system in New Zealand. Here’s what stood out for me:

1. Class Structures and Learning Styles

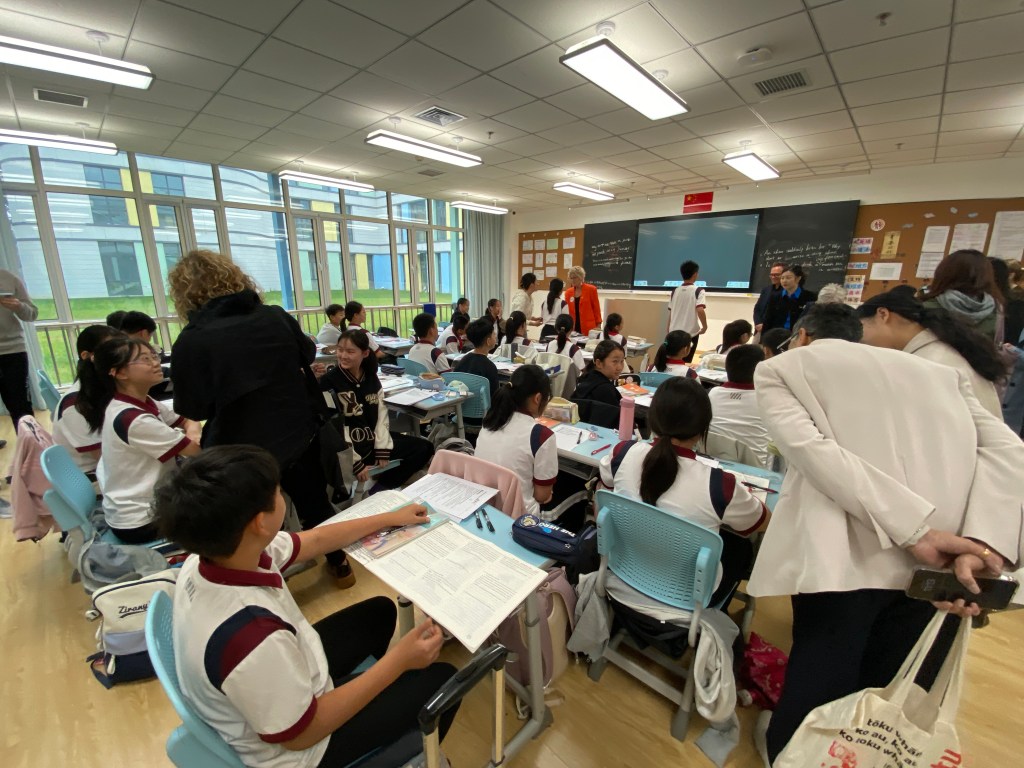

One of the first things that struck me was the sheer size of Chinese classes. Typically, a single room accommodates 48-50 students, all in orderly rows of single desks. It’s a striking contrast to the smaller, collaborative setups we have back home, where 25-30 students are encouraged to work together in groups, engage in discussions, and explore different approaches to learning. The Chinese approach is structured, organised, and formal, with each student largely focused on their own work. Most of the learning happens individually through workbooks, and while this setup is efficient, it’s a far cry from the flexible classrooms we’re used to in New Zealand.

One reason these large numbers work so well is the remarkable level of behaviour and discipline within Chinese classrooms. Unlike New Zealand, where PC4L systems (Positive Culture for Learning) and similar frameworks are commonly used to develop a positive classroom culture and maintain focus, such systems are almost unnecessary in China. The students’ respect for learning and adherence to classroom norms are deeply ingrained, allowing teachers to focus solely on instruction rather than classroom management. This cultural norm enables the smooth functioning of large classes without the behavioural interventions we often require in New Zealand.

2. Limited Use of Technology in Daily Classes

Another difference I noticed was the limited integration of technology in classrooms. In New Zealand, it’s common to see iPads, laptops, and digital tools in everyday learning across almost all subjects. But in the Chinese classrooms we visited, ICT was rare, reserved mostly for specialised subjects like computer science or robotics. Only one school had iPads accessible for classroom use. Afternoon choice programs allowed for more tech-based options, but it’s far from being the norm. This contrast highlights how New Zealand’s integration of technology supports flexibility, creativity, and tech literacy across the curriculum, while in China, it remains more specialised.

Reflecting on this, I couldn’t help but wonder if New Zealand’s liberal use of technology, as positive as it is, could be a double-edged sword. While devices open doors to interactive learning, they also bring easy distractions that pull students’ focus away from classwork—something as simple as a buzzing notification can derail focus. The ease of pulling up a digital device, when perhaps a good textbook could accomplish the same, might even reduce students’ ability to concentrate on in-depth tasks. China’s specialised approach may lack the everyday accessibility we have, but it also minimises the potential for off-task distraction, promoting a more concentrated learning environment.

3. The High Value Placed on Education

Education in China is nothing short of a high-stakes venture, and students are well aware of the pressure. At the end of Year 9, students face critical exams determining their future in education—only about 60% will progress to high school. And the stakes remain high as only about 60% of high schoolers make it to university. With these odds, both students and teachers work incredibly hard, keeping a keen focus on academic achievement. This contrasts sharply with the New Zealand system, which is more relaxed and non-exam-focused, particularly in the early years. Our students often know that if they miss an assessment or fall short, there are other options to catch up. While this offers flexibility, it’s hard not to notice the discipline and dedication evident in Chinese students.

The Chinese approach to education feels almost foreign to our students, teachers, and parents in New Zealand, where extensive study hours and intense competition aren’t prioritised in the same way. For us, education aims to balance academic growth with broader life skills, creativity, and well-being. But it does raise an interesting question: should we adopt a stronger emphasis on discipline and academic rigor to prepare students for an increasingly competitive world? While this doesn’t mean introducing high-stakes exams at every turn, perhaps there’s room to instill a deeper appreciation for discipline and commitment. Finding a balance between rigorous study and the flexibility of our current system might bring the best of both worlds, empowering students without overwhelming them.

4. International Cooperation is Key

One of the more unexpected observations was the importance Chinese schools place on developing international connections. Nearly every school we visited proudly displayed its “sister schools” from around the globe, showcasing its partnerships as badges of honour. These connections are seen as essential for broadening students’ and teachers’ perspectives and enhancing their school’s reputation. The importance of these relationships speaks to China’s forward-looking approach to education and its desire to incorporate global experiences.

In New Zealand, this level of formalised international cooperation is rare, and developing such partnerships has traditionally been a challenge. Perhaps it’s our laid-back approach or even our tall poppy syndrome, where standing out through formal accolades can feel at odds with our cultural values. As a result, while we may be naturally open to learning about different cultures, we tend to do so in a more casual, less structured way. Still, there’s something to be said for formalising these relationships, as they could offer both students and teachers in New Zealand meaningful exchanges and shared learning that goes beyond the day-to-day classroom experience. It’s an area that might benefit from a rethink, bringing a more intentional global lens to New Zealand’s education systems

5. Student Well-being and Physical Health

A feature in most of the Chinese schools we went to was an emphasis on student well-being, with each school hosting a psychology department. These facilities included padded aggression rooms complete with boxing gloves, sandboxes for emotional expression, and even robots for students to share their stories with. The facilities themselves looked impressive, but we rarely saw students using them, which made me wonder just how integrated these services are into daily school life.

Lunch was also taken seriously. Each student had access to a nutritious hot meal—balanced, low in sugar, and rich in nutrients. Combined with structured PE programs, it was clear that physical health is a top priority in China. Outdoor running tracks were the norm, and PE sessions seemed non-negotiable—sitting out or opting out wasn’t an option.

6. Language Learning and English Proficiency

Language learning is another area where Chinese schools place high value, with English taught from an early age. Many of the students we met were impressively fluent, often contrasting with the older generation of teachers who were less confident in English. While some of these interactions were a bit formal—students often had prepared scripts—many of them opened up when we stepped away from the formalities and their script! From almost all of the students I spoke wth there was a genuine curiosity about New Zealand and our way of life.

At the end of this journey, I couldn’t help but think about what New Zealand could learn from this approach. There are plenty of questions to ask but coming up with the right answer will prove difficult.

Based on what I saw, a typical 12-year-old in China has a healthy respect for school and education, the ability to converse in two languages, and access to a curriculum balanced across academics, arts, music, and physical education. And they get free highly nutritious meals each day! This well-rounded approach provides structure and discipline that’s deeply embedded in their daily lives. But there’s a noticeable level of stress and anxiety riding on these students’ shoulders; they’re keenly aware that their future career paths hinge on their school performance, creating an intensity most of our students in New Zealand can barely imagine.

In contrast, the average 12-year-old in New Zealand, is fluent in just one language, doesn’t get lunch at school, and encounters an educational landscape that has chopped and changed significantly in recent years. In New Zealand students experience a more relaxed atmosphere, emphasising collaboration, critical thinking, and group work over rote learning and testing. While anxiety is certainly present, its roots lie more in the pressures of social media and interpersonal issues rather than the outcome of school assessments. Here, students aren’t primarily focused on academic scores as the gatekeepers of their future—our system allows room to explore, regroup, and find alternative paths if things don’t go according to plan. It’s a divergence that raises important questions about the balance between academic rigor and well-being in shaping resilient, well-rounded young people.

Leave a reply to Diane Banbury Cancel reply