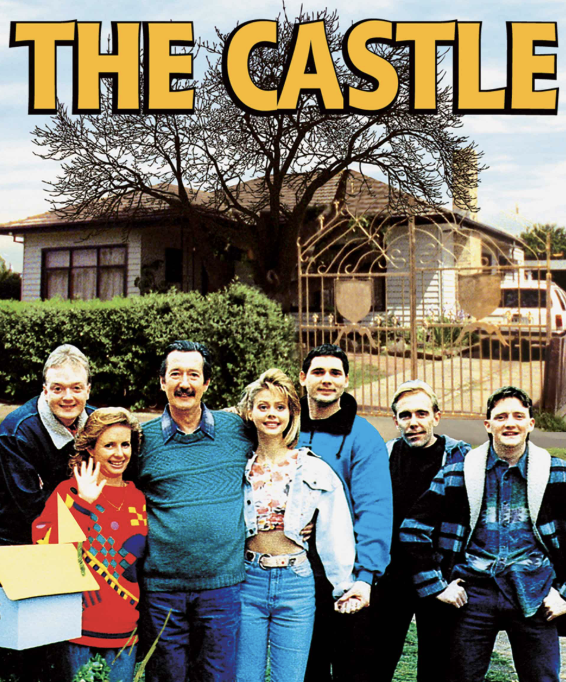

“It’s the vibe and ah, no that’s it. It’s the vibe. I rest my case.”

— Dennis Denuto, The Castle

It’s funny how often this quote comes to mind when we talk about teaching.

Ask someone why they use a certain strategy in the classroom, and you’ll often hear: “It just feels right,” or “The kids seemed to like it,” or my personal favourite, “It’s the vibe.” No solid evidence. No clear data. Just a strong belief that this must be the right way.

At Mount Intermediate, we’ve been asking some big, uncomfortable questions lately.

Why aren’t all our students making the progress we expect—two years of growth in one? What’s getting in the way? What’s working, and what’s just noise?

It’s the kind of inquiry that forces us to step back, breathe, and challenge some of our own deeply held beliefs about teaching and learning.

While reading Douglas Carnine’s paper “Why Education Experts Resist Effective Practices (And What It Would Take to Make Education More Like Medicine),” I found myself nodding more than I expected. He doesn’t pull punches—he challenges the whole field of education, especially our tendency to favour ideology, gut feeling, or whatever’s trendy over what the research actually tells us.

Carnine compares education to medicine. Now, that might sound like apples and oranges, but stick with it. In medicine, you wouldn’t ignore what the evidence says just because your favourite doctor “feels” like antibiotics work on a virus. There are checks. Trials. Data. Accountability. Yet in education, we often resist those same scientific guardrails.

One of the stories Carnine tells is about Project Follow Through—the biggest educational experiment in U.S. history. It looked at more than twenty different approaches to teaching young learners from disadvantaged backgrounds. The clear winner? Direct instruction. It outperformed other models academically and even in things like self-esteem. But here’s the kicker: many educational experts at the time ignored those results. Why? Because it didn’t fit the narrative they preferred.

That hits close to home.

At our school, we’re digging into why some students aren’t progressing in literacy and numeracy the way we’d hoped. And just like Carnine says, it’s easy to default to “hunches” or theories that feel right but may not hold water. Maybe we’ve clung to approaches that sound good but don’t actually move the dial.

What if, instead of starting from belief, we started with evidence?

What if we reframed teaching as a science-based profession?

That idea—one that’s popping up in places like The Science of Learning Substack—is gaining momentum. It suggests teaching should have a knowledge base like engineering or medicine. Not just stories, not just instincts, but a foundation of proven, replicable strategies built on cognitive science and learning research.

At Mount, that’s the lens we’re now trying to apply. Here are some of the questions we’re chewing on:

- What actual evidence backs the way we currently teach reading, writing, and maths—especially for kids who aren’t making expected gains?

- Is our professional learning lifting scientific literacy among teachers, or just recycling the latest edu-buzzwords?

- Are we creating a culture where staff feel safe (and encouraged) to ask, “Is this working?” and to seek real answers beyond opinion?

- What structures can we set up to weed out ineffective methods and scale up the ones that have consistent results?

- And how can we better use what we know from cognitive science—things like cognitive load theory, retrieval practice, and spaced repetition—to design learning that actually sticks?

These are not small questions. But they matter.

Because in the end, if our best answer to “Why do we teach this way?” is still…

“It’s the vibe”…

Then maybe it’s time to rest our case—and pick up the evidence instead.

Leave a comment