Can’t be bothered reading this? Check out the audio created on this topic using Google NotebookLM.

Being a middle leader in a school is a really important job. You’re right there, working closely with your colleagues, supporting students, and trying to make things better every day. But what does it really take to be effective in this role? I recently had the opportunity to explore this very question in a Masterclass led by Distinguished Professor Emeritus Viviane Robinson.

Viviane Robinson’s session helped us see that the most important goal, the proper purpose of middle leadership, is all about the students. It should be focused on improving the excellence and equity of student outcomes. This might sound obvious, but it was highlighted that when people interview for leadership jobs, they often don’t put student outcomes first – only about 1 in 4 candidates mentioned this as their main goal in some examples discussed. This tells us there’s a real need to keep our focus firmly on what benefits students most.

Think about what leadership actually is. It’s not just about having a title. Leadership is an influence process. Your ability to influence others comes from your relationships with colleagues, the value of your ideas and knowledge for solving problems, and to a lesser extent in education, your formal position. Middle leaders who have relevant knowledge and helpful ideas tend to have more influence. Your work involves juggling the day-to-day routines, dealing with the unexpected crises, and, often the hardest part, leading improvements that might shake things up a bit. If you see routine issues popping up constantly, like ongoing behavioural problems, that’s a sign they need to become a focus for improvement.

A huge part of being an effective leader, especially when you’re trying to make changes or tackle tricky issues, is building trust. Trust means you have a willingness to accept risk and vulnerability with others. Based on research, there are four main things that build trust: interpersonal respect, personal regard, competence, and integrity. Viviane Robinson emphasized that trust isn’t like money you put in the bank for later; it’s something you build actively while you’re doing the difficult work together.

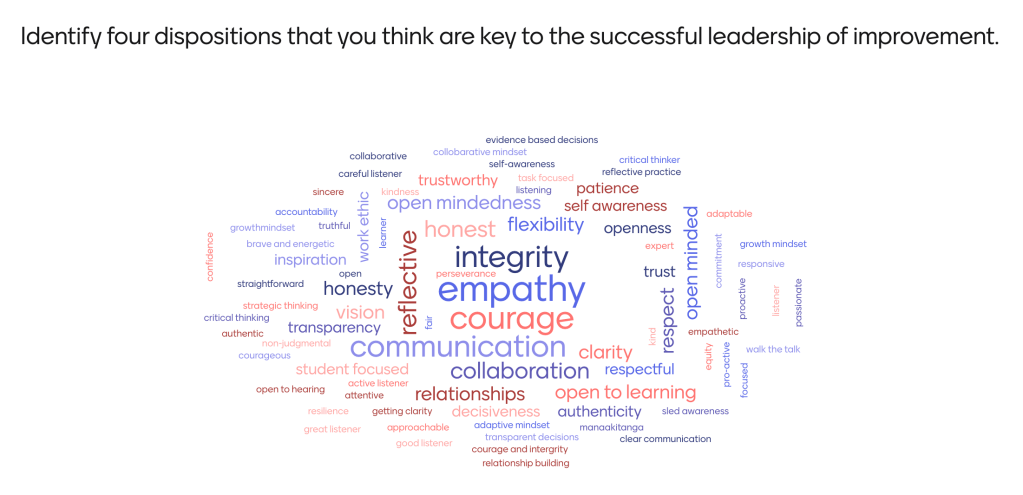

So, how do we build trust and lead effectively, especially when things get tough? It comes down to certain character traits, or dispositions. These are the inclinations that shape how we react in different situations. While many traits are important, the Masterclass highlighted courage, empathy, open-mindedness, and perseverance as particularly key for leaders.

Let’s look closer at two of these: courage and empathy.

Interpersonal courage is about taking risks and overcoming fears when you’re working with others to achieve those important educational goals. It’s being willing to challenge parts of your team or school culture that you believe are harmful. It means doing what you believe is right for your students, even if you think colleagues might not react well – like challenging stereotypes. Courage involves making yourself vulnerable; maybe you need to tackle a problem where you don’t feel totally prepared. What courage is not is being thoughtless, challenging people disrespectfully, protecting yourself by being indirect, or being rude. It’s something you learn by getting better at combining respect with taking risks and being open-minded. A school environment where it’s okay to take reasonable risks and learn from mistakes helps courage grow, while a place where people are scared of making mistakes can hold it back.

Empathy is about really trying to see the world as someone else might see it and then checking if your understanding of their feelings is accurate. It requires setting aside your own initial judgements about how others feel. It’s about remembering that behind the data are real students with real experiences. Empathy applies to the beliefs, attitudes, and feelings that staff and students have related to their roles in school. It involves identifying and checking in about the work-related emotions that might be present. What empathy is not is letting yourself be controlled or overwhelmed by others’ feelings (sometimes called empathetic distress). It’s not assuming you know exactly how someone feels, or judging if their feelings are valid. It’s also not prying into private lives. A really important point is keeping a balance between understanding others’ experiences and fulfilling your responsibilities as a leader. Empathy helps you understand, but it doesn’t mean others’ feelings automatically override what you need to do in your role.

Effective leaders often feel caught between two things: needing to tackle problems (the task) and wanting to keep positive relationships with colleagues. In education, there’s often a leaning towards prioritising relationships, which can mean difficult issues don’t get addressed. This can create a situation that was described as the ‘land of Nice’, where tough conversations are avoided, and critical feedback is rare, often because people are worried about causing upset or even losing staff.

This is where ‘courageous conversations’ come in. These are the skills you need to talk about difficult things while being both courageous and empathic. The key skills involved are advocacy (sharing your view), inquiry (asking to understand others’ views), and listening.

Here’s how to use these skills with courage and empathy, drawing from the Masterclass materials:

When you advocate your point of view:

• Do share your beliefs openly, but present them as your view, open to being challenged.

• Do respectfully share your relevant feelings about yourself and others.

• Do give clear reasons, evidence, and examples for your beliefs and feelings.

• Don’t hide beliefs or feelings just because they might cause a negative reaction.

• Don’t state your opinions as if they are absolute facts.

• Don’t just talk in vague terms without explaining what you mean with examples.

When you inquire to understand what others are thinking:

• Do show respect by being clear about what you want to understand and why.

• Do ask genuine questions – questions where you don’t already know or assume the answer.

• Do explain why you are asking the questions.

• Do create space for others to respond by pausing and listening.

• Do actively seek feedback on how others see things, including any doubts or disagreements they might have.

• Do look for information that might challenge or disprove your own views.

• Don’t ask leading questions just to protect yourself or guide someone to the answer you expect.

• Don’t ask questions without giving the real reason for asking.

• Don’t only listen for things that support what you already think.

When you listen with courage and empathy:

• Do listen with a clear focus related to your responsibilities in your role.

• Do make sure you listen to all relevant views.

• Do summarise what you’ve heard, especially when things are complicated or people disagree, to make sure everyone is clear.

• Do check that your summary is accurate by asking others if you’ve understood correctly.

• Do genuinely express thanks for what you’ve learned from hearing others’ views.

• Don’t just listen to everything without considering what’s relevant to your role.

• Don’t decide who to listen to based on your prior opinions of them.

• Don’t give a summary that leaves out information you find inconvenient.

• Don’t keep interrupting unless there’s a very clear, justifiable reason.

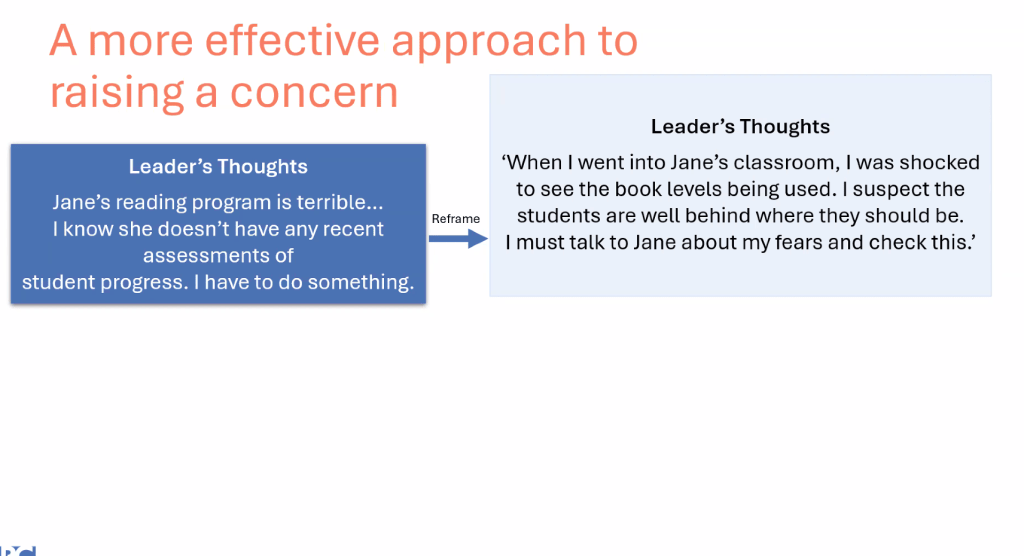

A really powerful idea shared was that the key to better conversations often starts with reframing your own thinking before you even speak. Instead of internal thoughts like “Jane’s reading program is terrible,” try reframing it to something based on observation and open to exploration, like “I was shocked by the book levels and suspect students are behind”. This kind of internal reframing naturally leads to better ways of talking, like saying, “I got the impression from book levels that students might be behind where I would expect”. This approach invites a conversation to understand different perspectives rather than just telling someone they’re wrong.

The good news is that these leadership dispositions, like courage, are not fixed traits; they can be learned. People often avoid courageous conversations not because they are fundamentally timid, but because they haven’t learned how to express concerns respectfully. With practice, even someone who feels naturally timid can develop into a courageous leader.

Ultimately, effective middle leadership circles back to that core purpose Viviane Robinson highlighted: making things better for students. By keeping that goal in sight and actively working on developing dispositions like courage and empathy through practising skills like advocacy, inquiry, and listening, middle leaders can build stronger trust, handle tough conversations more effectively, and truly drive positive change in their schools. Taking time to reflect on how much of your effort is genuinely focused on improving student outcomes is a valuable step for any middle leader.

Leave a comment